As teachers, we think a lot about teaching and learning, spend hours developing resources and hone our classroom practice so that students can get the most out of the hours they spend with us. However, rarely do we give any thought or attention to our own development and learning. This, I am realising more and more, is a serious problem. Firstly, it means that for a good many staff there are limited opportunities for them to improve and grow. But the biggest issue is that a lack of self-development damages students: those who do not learn themselves are going to find it more difficult to effectively model the process of learning with their students.

So, how to we solve this problem and get teachers learning? At Copleston High School we have just embarked on a process that will turn all our classroom staff (teachers, CTAs and Cover Supervisors) into action researchers. We took the following approach:

STAGE 1. AND OUR SURVEY SAID…

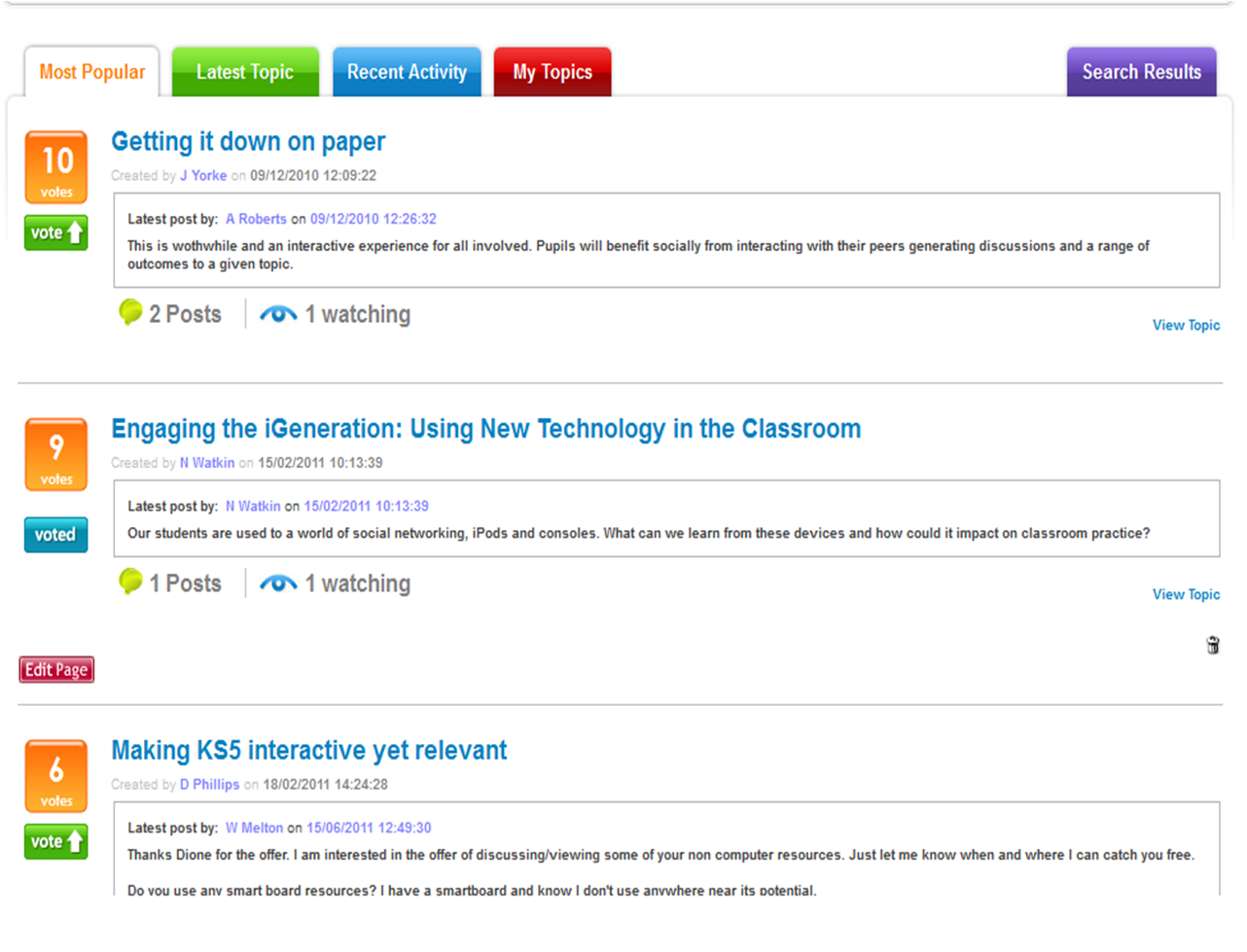

Our first action was to start a dialogue with staff and take their ideas about teaching and learning seriously. Therefore, we set up an area on our FROG VLE where staff could suggest what the school should focus on and then vote on which were the best proposals.

STAGE2. REVAMP LEARNING & TEACHING GROUP

We have a termly Learning & Teaching Group Meeting to which each department sends a Rep. Up until 15 months ago, its role was to discuss items that appeared on an agenda, which was rarely populated by anyone else other than senior leaders. We took the decision in October 2010 to offer them an alternative: carry on as we had been, or use the time to form action research groups. The vast majority opted for the latter and so we took the top five priorities from the staff survey and turned them action research titles. Members of the Teaching & Learning Group then divided themselves up according to interest and started researching.

I wanted to create a buzz about action research, get people innovating so that others might follow (see Geoffrey Moore, 1991). I love the way Seth Godin talks about this in his TED talk:

STAGE 3. RE-BRAND PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

We now had five action research groups with interesting findings that they could share. After an insightful trip to Cramlington Learning Village and talking to staff there we adapted their idea of holding an internal conference. We started organising conference packs, speakers, food, etc so that it had the feel of a real conference, but it would be for our staff about our development. We felt this step was important, because it would signal a new direction and new expectations from staff. We called our conference Copleston Sauce: Open, taste and Love Learning (a title created by 7LM – my Year 7 ICT group – they even designed the logo).

STAGE 4. SELL THE IDEA OF ACTION RESEARCH

On the first day of the conference (Tuesday 3rd January 2012) we split the whole teaching body into groups of five and asked them to sit together at round tables in the main hall. This was not a shock, we published lists and an explanation before the event and held two briefings in December. We started by talking about the reason why the school exists: to serve the community in which it sits. We then explored, how we can exemplify the idea of community in our practice. We talked about teachers forming communities in order to learn so that they could mirror and demonstrate amongst themselves what they expected of students in the classroom. We talked through the idea that the school community needs to have an andragogical and pedagogical strand in order to grow (see David Price’s blog on the Learning Futures Project). This, we explained, was why we wanted them to form small learner communities and conduct some action research.

STAGE 5. HERE’S ONE I MADE EARLIER

Next, we got each member of the new learner communities to go to one of five workshops based around the research topics conducted by the members of the Learning & Teaching Group. This enabled us to model the process with staff and plant some seeds in their minds.

STAGE 6. START PLANNING

With the help of a protocol we designed specifically for the occasion, we got the learner communities to start talking amongst themselves and deciding what would be the focus of their action research. It was a risk constructing the groups and not allowing total freedom of choice, but the principle of learning from others and mixing up staff with different roles and skills was an interesting experiment – it will be interesting to see the results of the evaluation when it comes back. At this stage we felt it was important to drive home the community angle and to make staff even more aware of the potential within the school.

The initial response was incredible. The questions being posed were fantastic and the level of engagement from staff was amazing – the conference ended at 4:00 pm on Wednesday 4th January 2012, and 20 minutes later there were still staff in the hall discussing their action research. The sharing has continued on twitter with people suggesting resources and links and it was happening across departments and between staff and CTAs. We feel that the freedom for each learner community to determine its own title was important in building ownership of the process. It has created a genuine enthusiasm for action research and a platform on which we can build a school community that truly has learning at its heart. What we have done is in no way unique and borrows heavily from work already carried out by Learning Futures Project, High Tech High in California, Cramlington and the work of Dylan Wiliam. However, it is a big step forward for us and we believe is moving us into a completely new space in terms of development

The challenges we now face are helping staff to realise their plans in the coming weeks and to establish a model for making action research a key component of the Professional Development programme year after year. We really want the conference to happen again next year and for the most part to be run by the Learner Communities. What the conference this year has shown us is that teachers really do need each other to develop and to enable them to thoroughly practice what they preach.