There is an abundance of research, for example here, here and here, that point to the idea that reading comprehension and academic achievement can be vastly improved, and socio-economic gaps closed, by consistently increasing the amount of academic knowledge students learn starting from primary school. These theorists also suggest that knowledge builds on knowledge, cumulatively. So the more you read and learn about the world, the more you will be able to grasp. A good summary about the idea of core knowledge and the link to literacy comes from ED Hirsch, who states that:

Nearly all of our most cherished ideals for education – from reading comprehension and problem solving to critical thinking and creativity – rest on a foundation of knowledge.

As a parenthesis, in case you’re interested in a second perspective, see this critique of Hirsch. Some of his ideas can be interpreted as a tad elitist e.g. his books ‘What your child needs to know…’ series can testify to that notion. However, I still agree with his basic premise above.

A Knowledge Curriculum

I am interested in what we can do with a research guided approach to ‘knowledge’ in the classroom, beyond testing. Many may be familiar with Daniel T Willingham’s thinking around knowledge and intelligence. Willingham states:

..knowledge does much more than just help students hone their thinking skills: It actually makes learning easier. Knowledge is not only cumulative, it grows exponentially. Those with a rich base of factual knowledge find it easier to learn more—the rich get richer. In addition, factual knowledge enhances cognitive processes like problem solving and reasoning. The richer the knowledge base, the more smoothly and effectively these cognitive processes—the very ones that teachers target—operate. So, the more knowledge students accumulate, the smarter they become.

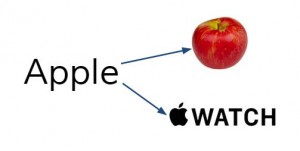

Let’s look at a concrete example of how this would work in practice. A weak reader with some background knowledge of the read topic will score higher than a stronger reader with little or no background knowledge of the topic. Why? Because, as Willingham has found, factual knowledge matter improves literacy and critical thinking skills. So with your own background knowledge, consider the word ‘Apple’. What comes to mind, a piece of fruit, Apple Watch or perhaps apple pie? But, your background knowledge goes deeper than that, of course. Let’s take a look at how language is further made complex by the absence or presence of background knowledge by examining the example below:

Let’s look at a concrete example of how this would work in practice. A weak reader with some background knowledge of the read topic will score higher than a stronger reader with little or no background knowledge of the topic. Why? Because, as Willingham has found, factual knowledge matter improves literacy and critical thinking skills. So with your own background knowledge, consider the word ‘Apple’. What comes to mind, a piece of fruit, Apple Watch or perhaps apple pie? But, your background knowledge goes deeper than that, of course. Let’s take a look at how language is further made complex by the absence or presence of background knowledge by examining the example below:

The hunter said “There’s a grouse across that field maybe 100 yards away.” His friend said, “well, shoot.” The sentence does not mean “fire your gun.”

Background knowledge = shotguns aren’t accurate at 100 yards. A grouse that has flown from cover is gone. “Well, shoot” means “too bad we missed it”. – D.T. Willingham

This is why “in-jokes” are only funny to those with the background knowledge to understand the underlying meanings.

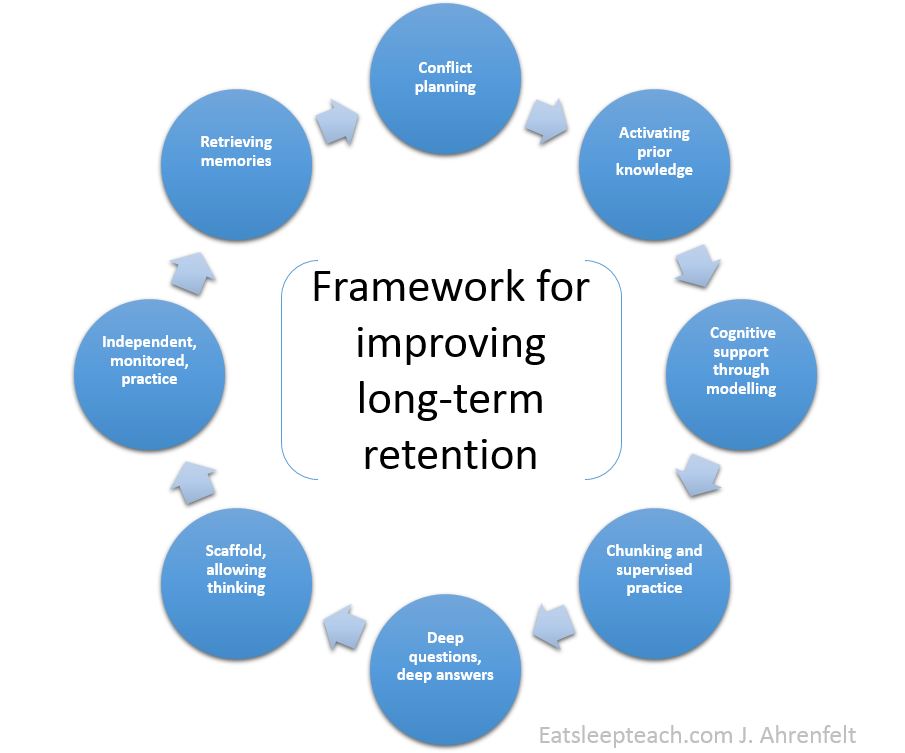

So if we believe that factual knowledge is the medium of understanding, then what’s the problem? The problem for students lie in retaining this knowledge. Unfortunately for us humans, our working memory – the one we use remember and use relevant information while in the middle of an activity e.g. following instruction or remembering a phone number – is very limited. This is an area I have devoted some time to explore, particularly in terms of testing and spacing, but I’ll share my experience on that at a later date. For now, I’d like to share a pedagogical framework I have developed which looks to maximise retention of long-term memory for students; a ‘wrapper’ for a consistent approach to the way we teach – whilst encouraging teacher autonomy and teacher creativity. I have accessed recent research on core knowledge and instruction, all of the sources are listed at the end of this post.

There are five subjects in my faculty: History, Geography, Sociology, Law and Government and Politics. As a result, there’s a real opportunity to align our curricula according to the framework below. Here’s how it works.

Conflict Planning

Conflict Planning

Our lessons are framed around a ‘hinge’ or key question which students investigate throughout the lesson. These questions provide a sense of meaning to the learned content and, if planned with conflict in mind, may make our lessons more memorable. Hinge questions work for any subject and are ideal for challenging students to think throughout the lesson. The ‘why, why, why, why?’ helps to provide tension in the learned content. However, in order for students to retain the new knowledge in their long-term memory, further tension is needed. If we treat each lesson like a good story with its predictable structure (see previous post on the power of stories in lessons), which focuses on the 4Cs of causality, conflict, character and complications, then this will help to refocus students’ attention on the core meaning of the lesson and therefore more likely for new knowledge to be added to their long-term memory.

Good modelling would ensure that the central meaning of the lesson is maintained by using concrete but subject relevant information.

Activating Prior Knowledge

This is of course a key component in any good lesson plan so that the teacher knows where to pitch the learning. However, activating is more than checking if they remember. When I use the phrase ‘to activate prior knowledge’, I am referring to a moment in the lesson when students use techniques to retrieve knowledge. This means that teachers need to train students ways to remember facts. In order to teach them memory retrieval skills I recommend you read any of the sources from this list:

- How to develop a perfect memory (superb online book) by D. O’Brien

- Moonwalking with Einstein J. Foer

- Feats of Memory Anyone Can Do J Foer’s TED talk

- What will improve a student’s memory? (see practical strategies towards the end of the article) D.T Willingham, American Educator.

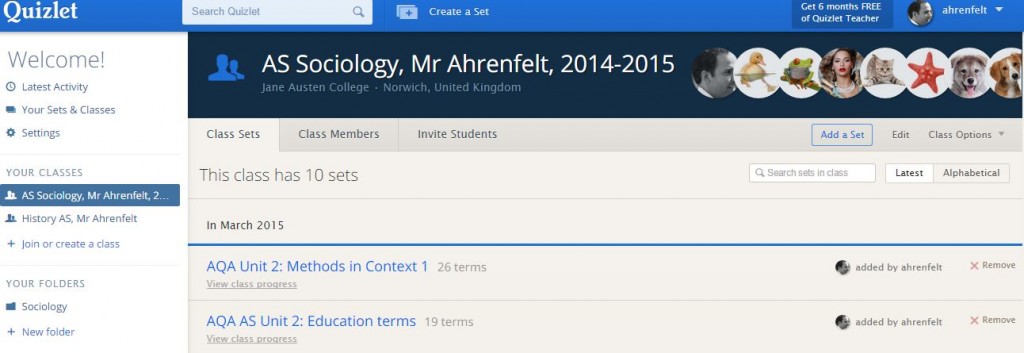

One simple way to encourage students to practise memory retrieval is to engage them in gamification via tools such as Memrise or Quizlet. The latter is particularly good as tests are quick to set up and students really enjoy taking them due to their competitive structure. The real strength of these types of tools is the opportunity for self-testing, again and again.

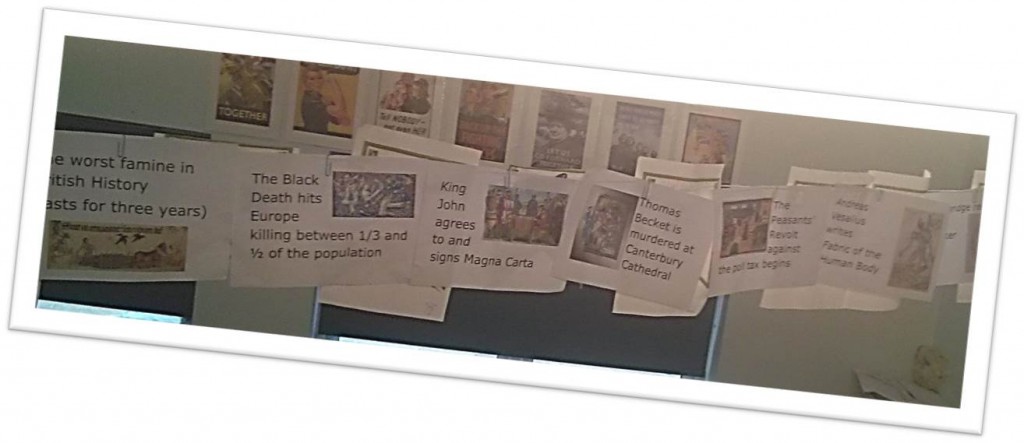

We are also exploring using Knowledge Vaults with students, particularly with exam groups. This is a document which provides an overview of required knowledge we want students to remember. The Knowledge Vaults differ depending on the subject and Unit but would for example include terminology, quotes (from historians, sociologists or research), key studies and a timelines. Our Knowledge Vaults accompany the testing framework well, as you can imagine, and is an active component in the way we assess mastery.

Cognitive Support through Modelling

To make sure we offload as much of the cognitive load as possible, good teachers provide good quality modelling of tasks or activities e.g. working through examples on the board with the support from students. Some use examples that are relevant to students’ lives and to make the subject matter more enjoyable e.g. when teaching about the October revolution the teacher gets students to create an animation using stop-motion, which the teacher demonstrates how to do. Daniel T. Willingham reasons that “…your memory is not a product of what you want to remember or what you try to remember; it’s a product of what you think about“. According to this argument, student would therefore remember how cool it was to create a stop-motion animation rather than, say, the causes of the revolution. Good modelling would ensure that the central meaning of the lesson is maintained by using concrete but subject relevant information.

Effective scaffolding teases out understanding rather than limiting it; creates opportunity rather than slowing thinking down; challenges students to struggle through their thinking.

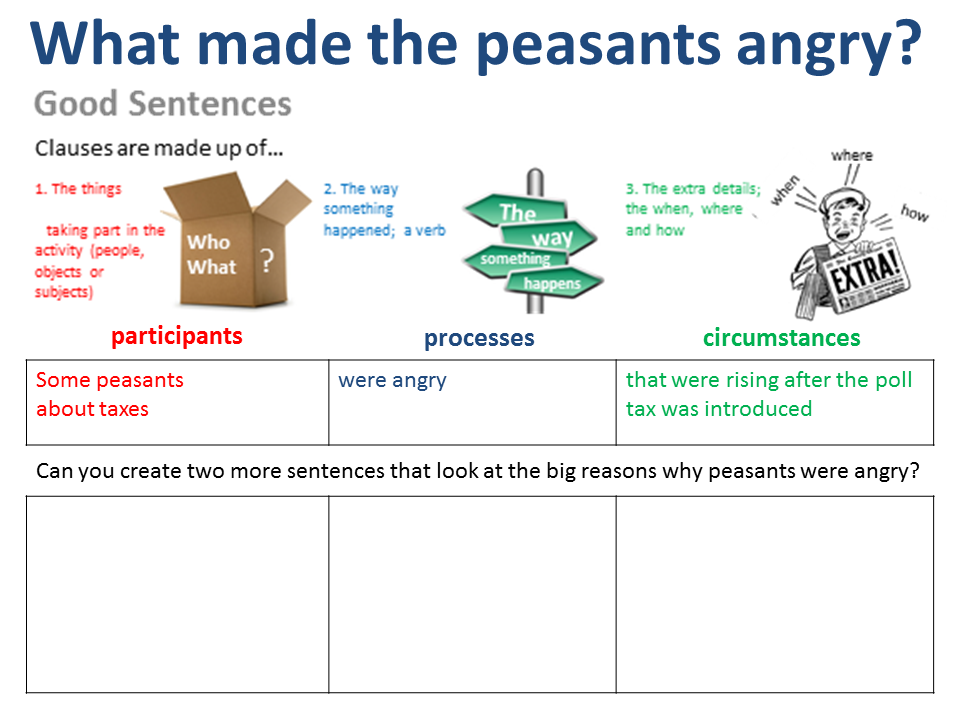

Chunking and Supervised Practice

This is an essential part of the lesson. Our working memory is too limited to be able to deal with the vast amount of facts that teachers want students to learn. By splitting the new knowledge into manageable chunks, students are capable of working through each chunk by step without memory overload. After each new part has been looked at, students should practise with guidance from the teacher or peers. This is a crucial part of the lesson so that the new knowledge is not forgotten, or that misconceptions are not remembered. Techniques for supervised practice could include using graphic organisers to do various activities like 100 word summaries, venn diagrams, or by asking pairs to reason through a problem, with another pairs listening in, to gauge how far they have understood.

Supervised practice is key and links directly to the next step:

Deep Questioning, Deep Answers

In ‘Teach like a Champion (chapter 1)‘, a teacher favourite across the globe nowadays, Doug Lemov shows how exceptional questioning can encourage the most stubborn student (or shy) to think hard; think deep. I think this strategy can be further improved by challenging students to support each other to build a deep answer. This is where the whole class actively listens and then provides examples of how to improve the verbal answer e.g. using subject specific terminology, connectives, examples and so on. Whilst this is a worthwhile cognitive activity in its own right, it also allows teachers to check understanding across the class, sort misconceptions and drive learning forward by showing students how to connect their knowledge together – both factual and skill(s).

Scaffold – allow thinking

We had an educational advisor come into our school to review teaching and learning (we are a Free School). One thing she picked up on was how different teachers provide support. The advisor commented that good scaffolding occurred throughout most of the school but there were instances when ‘students [had] no chance to think for themselves’. I’ve worked in several schools over the years and this way of scaffolding is not isolated to only some of our teachers. Because we want to makes sure all students progress, we differentiate and provide challenge where we require. Effective scaffolding teases out understanding rather than limiting it; creates opportunity rather than slowing thinking down; challenges students to struggle through their thinking.

Independent Monitored Practice

At this point in the lesson students know what they are doing and will spend time on their own focusing on completing a set task. Unlike supervised practice, independent practice involves more time for students to think and work without the support from peers. It does not really mean allowing students to ‘get on with it’ for three lessons without supervision. Regular reviews will take place to check understanding. Supervision of independent practice often takes shape as questioning and quick pitstop checks.

Retrieving Memories

By reviewing what students have learned during regular intervals e.g. weekly and monthly, we help them to strengthen their memories further. In fact, retrieval practice goes even further and:

- Improves students’ complex thinking and application skills

- Improves students’ organization of knowledge

- Improves students’ transfer of knowledge to new concepts

So, retrieval doesn’t only help to improve long-term memory, it also increases our understanding. As Barak Rosenshine explains:

Students need extensive and broad reading, and extensive practice in order to develop well-connected networks of ideas (schemas) in their long-term memory. When one’s knowledge on a particular topic is large and well connected, it is easier to learn new information and prior knowledge is more readily available for use. he more one rehearses and reviews information, the stronger these interconnections become. It is also easier to solve new problems when one has a rich, well-connected body of knowledge and strong ties among the connections. One of the goals of education is to help students develop extensive and available background knowledge.

There are numerous ways of encouraging retrieval practice some of which have been mention above in ‘Activating Prior Knowledge’. This way of connecting knowledge, exponentially growing one’s understanding, is particularly effective if built into the curriculum for example via tests or an exam strategy that spaces learning across time with several opportunities to practice.

Next post I will explore how we will use the framework for maximum impact.

References and Further Reading

What makes great teaching? Review of the underpinning research by Robert Coe, Cesare Aloisi, Steve Higgins and Lee Elliot Major, Durham University and the Sutton trust, October 2014

Ask the Cognitive Scientist: What Will Improve a Student’s Memory? in AMERICAN EDUCATOR | WINTER 2008-2009 by Daniel T. Willingham

Why Don’t Students Like School? by Daniel T Willingham

How Knowledge Helps: It Speeds and Strengthens Reading Comprehension, Learning—and Thinking. By Daniel T Willingham, American Educator, Spring 2006

You Can Always Look it Up’… Or Can You? by E.D. Hirsch., American Educator (Spring 2009)