In the last post on differentiation I outlined the struggle I have gone through with differentiation and how oracy – when tackled in a ‘expert’ way (advocated by Ron Berger) – can give students the confidence to communicate and believe that they can do so effectively. In this post I want to explore how we transfer confident talking into confident writing.

We all know that some students struggle to put their ideas down on paper and that it hampers their progress in learning. Also, it affects their ability to enjoy the lessons we teach, because they ultimately know that they will not be able to create an effective end product. At the other end of the spectrum, there are students with great literacy skills who can’t achieve, because they find it hard to deconstruct second order concepts and historical writing. I will tackle these in the next two posts.

Understanding How To Write

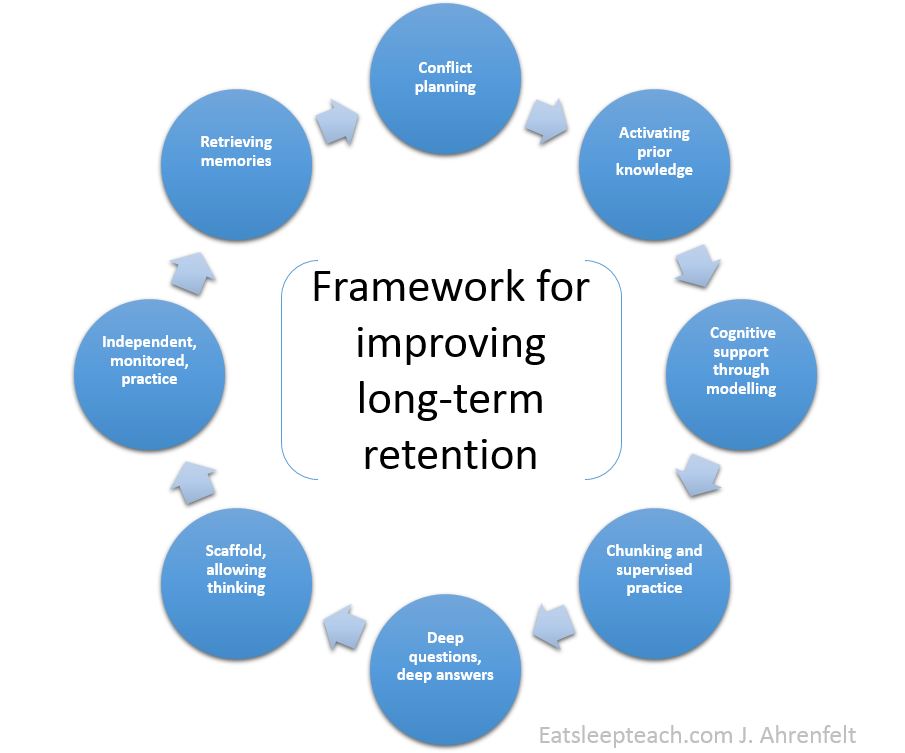

Planning for progression in writing requires, in my opinion, a vast amount of preparation. The first stage is to make sure that students have a sufficient knowledge base to draw from. Johannes has recently written a brilliant post on this (see Maximise Retention of Students Long-term Memory Part 1). Students who know ‘how’ knowledge builds up and how to deploy it will be more confident writers. Having looked at the attitudes of reluctant writers from Year 7-11, I am convinced that a secure knowledge base is an essential precursor for confident writing. I will not go into vast amounts of detail about why this is so important here, instead, I will just give three short examples of how knowledge can be built up and constructed throughout the year.

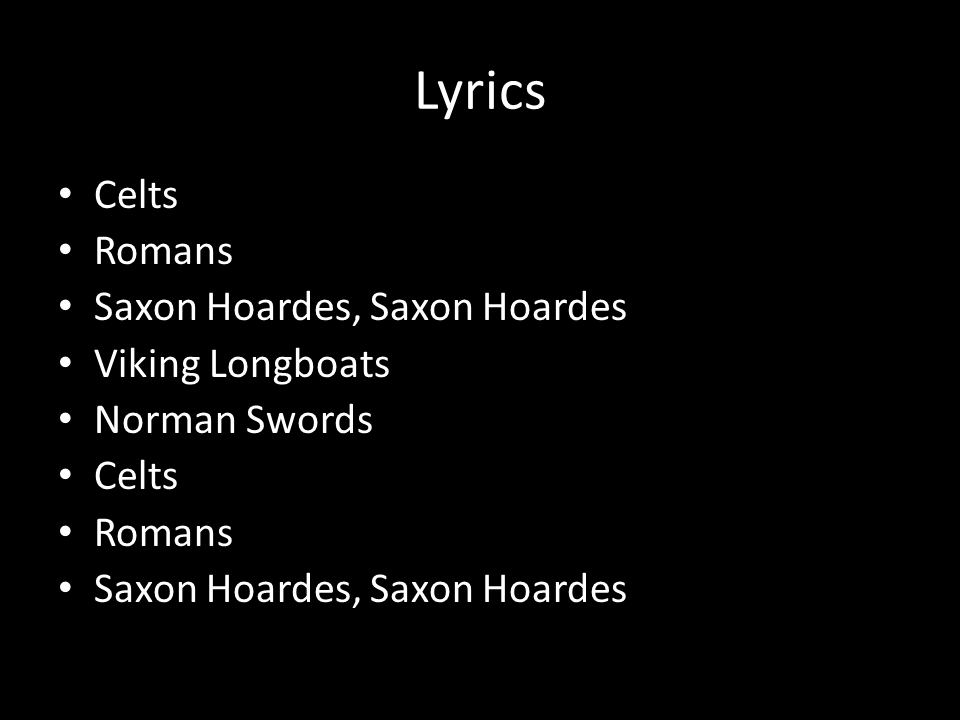

Raiders and Invaders Song to Establish Chronology

The raiders and invaders of Britain can be sung to the tune of ‘Heads, Shoulders, Knees and Toes.’ Singing it regularly as you go through the units with students helps them to establish a chronology, especially when accompanied by actions:

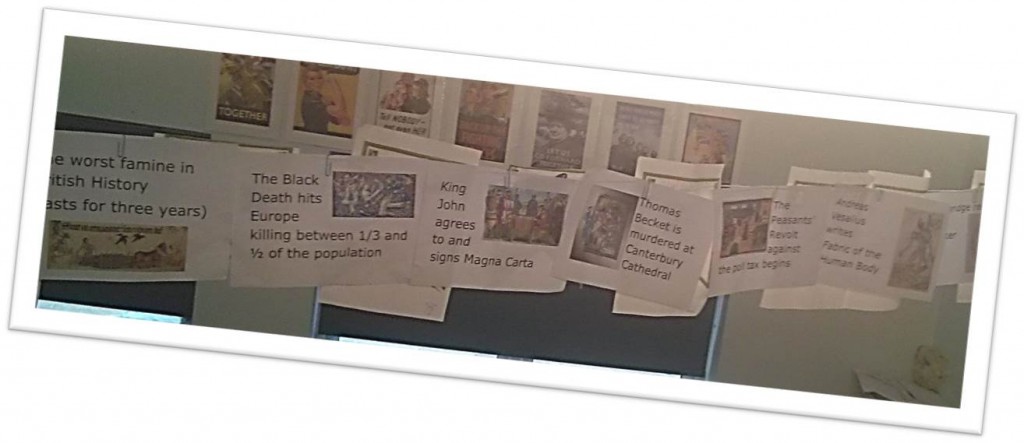

This process can be strengthened by using a class timeline. At the start of the year I gave Year 7 a 21 event timeline and asked them to decide on the order they thought the events went in. Inevitably there were errors, but we have been correcting these in plenaries as the year has progressed. Asking the question, “So, do you still think our timeline is correct? Do we need to move something?” has enabled students to think carefully about what we have been studying on a regular basis and to review their historical knowledge.

Further to this, quick quizzes that add layers of complexity can also help. For example, start by testing the five groups, then move on to the dates that correspond to their dominance in Britain, next add in key individuals and then put key events in there too.

Planning for Knowledge

This year I have tried to map out the contextual knowledge that students will need to understand a key event and then to include that knowledge at an earlier point in the curriculum, so that students get a chance to experience it and work with it so that it is ready to recall when needed. Christine Counsell has been working on this concept and states understanding requires ‘fingertip knowledge’ and ‘residual knowledge.’ Here is one example of how I have tried to make this work:

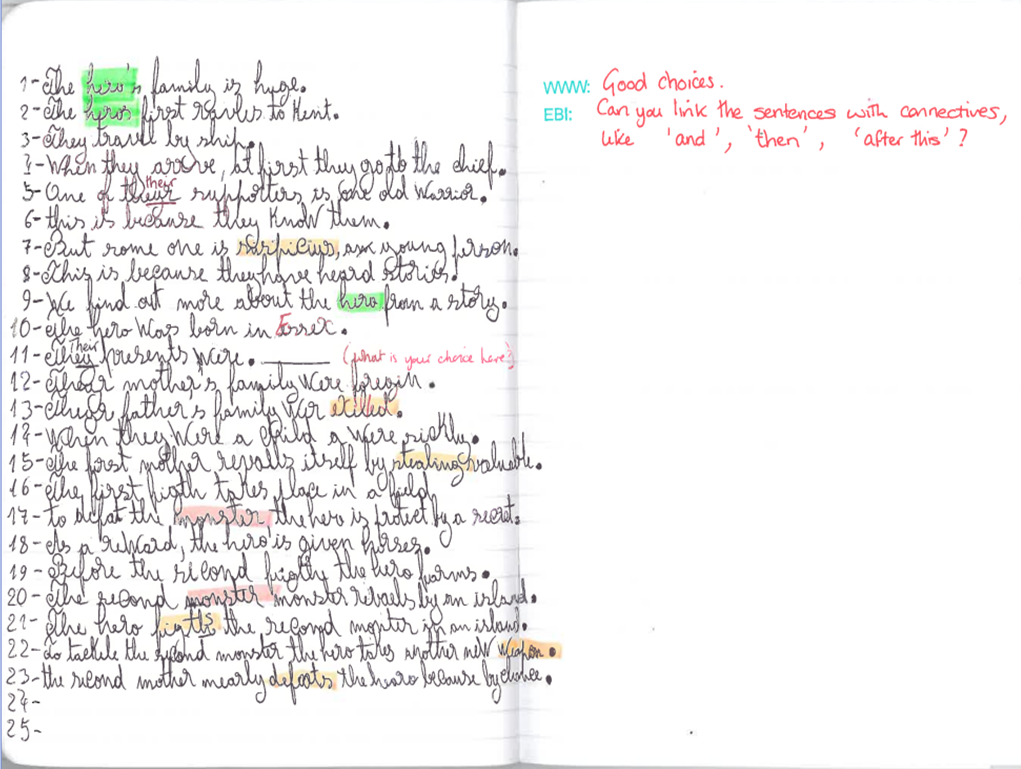

I took an epic poem resource from the brilliant Thomas Tallis School Creativity Lab and made it into a historical exercise, by borrowing from texts like Beowulf (download epic_generator Saxons here). I asked students to create an epic poem for homework. Many did a great job and enjoyed the random nature of throwing dice to determine elements of the story. It was a fun way to get them engaged in Saxon culture. After marking the poems I got students to highlight three things in the text: positive characters, negative characters and emotive or revealing words. Below is a sample of the work from an EAL student:

We then went on to analyse what type of story it was and why the Saxons might have told these kind of tales, especially since it did not really fit with the evidence of the Saxons that we encountered in the archaeological evidence). Now that the students were armed with their own epic poems and an understanding of why they were written, they found it easier to comprehend why Harold Godwineson did not follow his brother’s advice ad remain in London when William attacked. This residual knowledge of Saxon epic poems helped them to grasp the choices made in 1066.

This kind of curriculum planning takes time, but it is essential to tie up knowledge so that students find it easier to draw on it and create better answers. Students get ‘blocked’ when they are not confident of the knowledge they need and whatever techniques for writing you teach them will be in vain if they can’t access the knowledge to create their writing.

Word Games

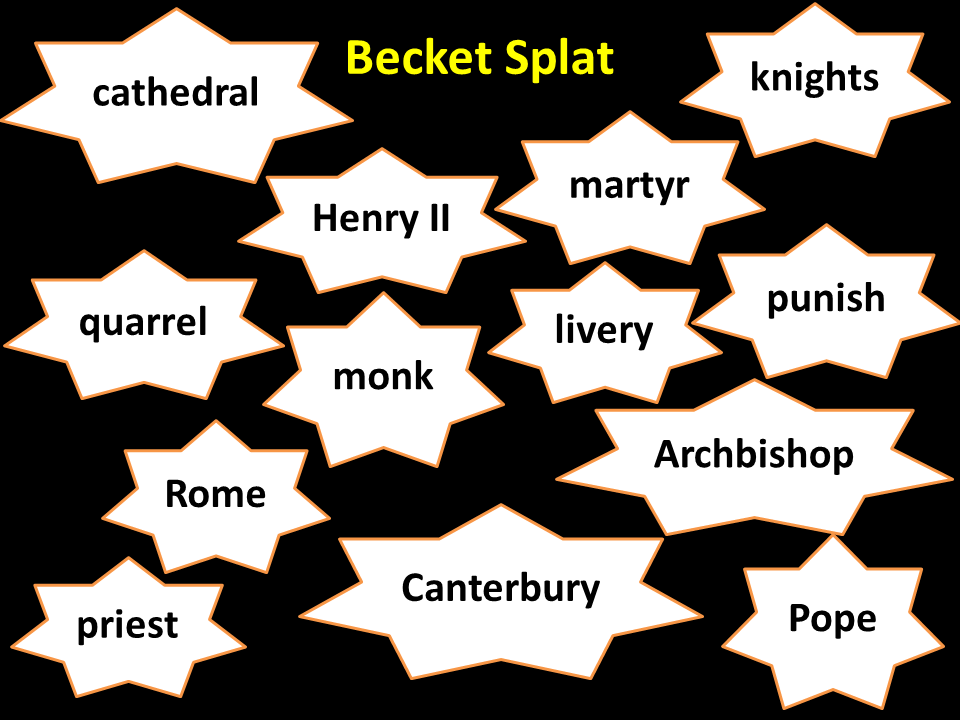

I would like to thank Don Cumming (@jackdisco) for many of the ideas that I have used to strengthen this part of my teaching. His session at Berkhamsted Learning Conference (TLAB 2015) was inspiring. The following example builds on the idea of instilling confidence that I talked about in the previous post of Differentiation (see ). The game ‘Splat’ requires students, in pairs, to race against each other to find a word that goes with a definition that you give. There are lots of ways to involve students: playing, giving their own definitions, suggesting and writing new key words. Activities like this reinforce the core knowledge of each topic.

I hope these three examples give a flavour of the knowledge work that can be done to prepare students for quality writing.

Structuring Writing: Functional Grammar

The remainder of this post is centred around my experiments with Functional Grammar. I am not going to give background into the strategy as Lee Donaghy does it brilliantly on his site ‘What’s language doing here?‘ What I want to add is why I think it is making a difference to many of my students and to share some of the strategies I have been using.

Firstly, to help explain the concept to students I created some props:

These were then used with classes to visually show the different parts of a clause and how they work. Elements of a sentence were written on post-its and students had to identify which elements they thought they belonged to. Having subject vocabulary broken down in this way was useful and scaling up discussion, from individuals, to pairs and then fours meant that students could explore what a participant, process and circumstance looked like. Ensuring that there was at least one example of each type in a four meant that whole sentences could be constructed, deconstructed, explained and then put back together. For example, the sentence…

John Ball preached radical sermons while travelling around East Anglia

can be broken down into…

The ‘Who/What?’ elements (participants) John Ball radical sermons

A ‘The Way Something Happens’ element (process) preached

The ‘Extra/Extra Information’ (circumstances) while travelling around East Anglia

These elements were then sorted and stuck to the relevant prop. Each prop as held by a student and they had to make a mental note of any element they thought was incorrectly placed. This added another layer to the discussion and deepened the understanding of the terms.

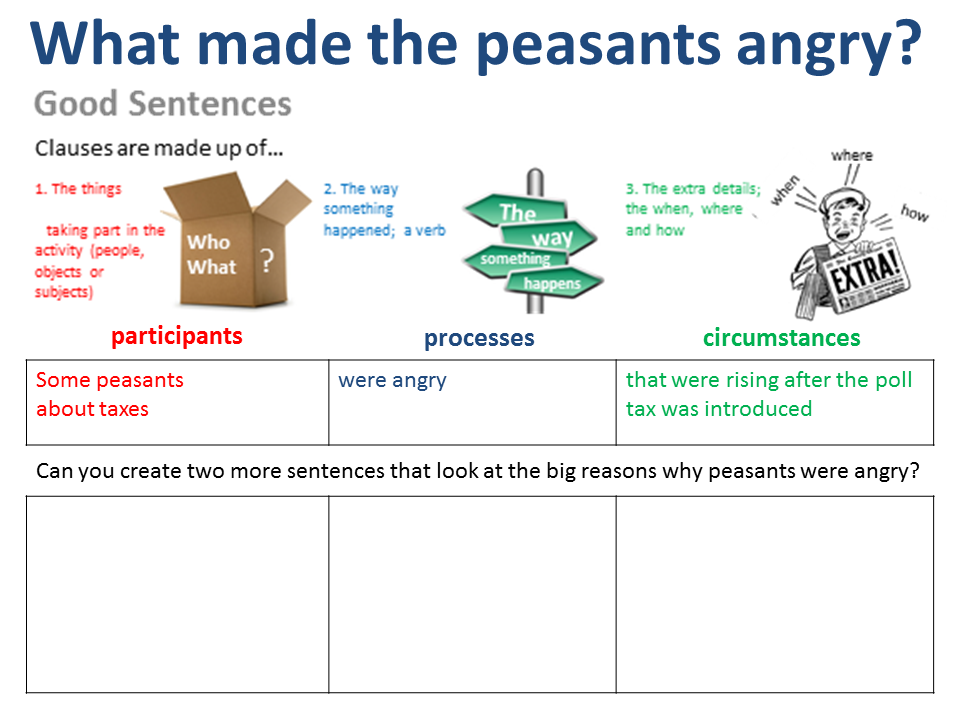

Students were then able to practise their writing in groups using A3 grids like these:

Once they were confident, they could tackle their own paragraphs and write a final draft in their books. Use of highlighters to identify the three elements immediately shows if they are using the structure well. Asking students if they can see a ‘Sea of Green’ in their work helped them to focus on the History (and, yes, I did play them a clip from ‘Yellow Submarine’ – 2:00-2:05 mins)

Explicitly teaching Functional Grammar has had a direct impact on the work that students are producing. Sentence structure has improved and, most importantly, their work is more historical. Focusing on the ‘Extra’ information has meant that students are adding key dates and locations to their work in a way that they were not consistently doing before.

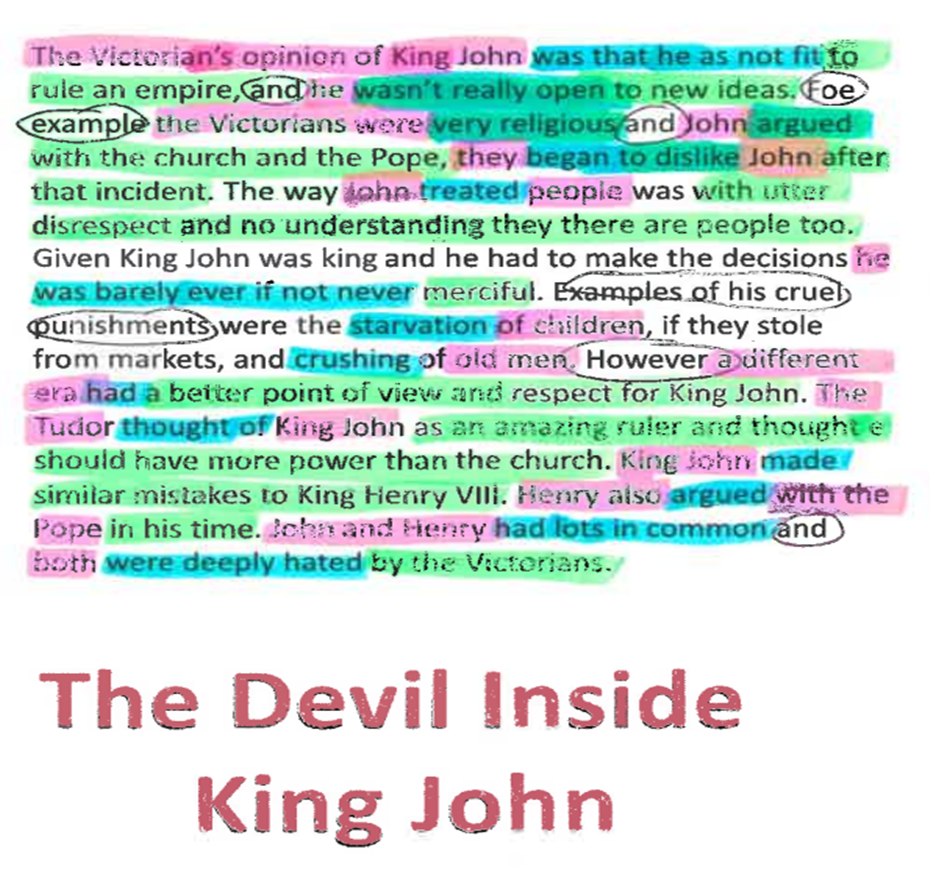

Take this example from an SEN student. Before using Functional Grammar to structure written work they were creating paragraphs like:

Edward the Confessor is King. Harold is ship-wrecked. He is rescued by William. Edward dies and Harold makes himself King. William prepares an invasion. He is delayed, but then the wind changes so William lands at Pevensey.

There are some clear issues with this paragraph about the causes of the Battle of Hastings, not least that it lacks historical depth. Also, some sentences are very short and do not deal with the whole subject matter. Now, consider this later piece of work by the same student. It is the final piece of work in the unit and represents several lessons of oracy, Functional Grammar and VCOP input:

Not only is the sentence structure better, but there is more historical depth to the answer. In addition, the student is clearly able to identify which elements are ‘Who/What?’, which are ‘The way something happens’ and which are ‘Extra, Extra Information.’ The reason why I think this matters so much is that it not only improves literacy, but also contributes to creating better History.

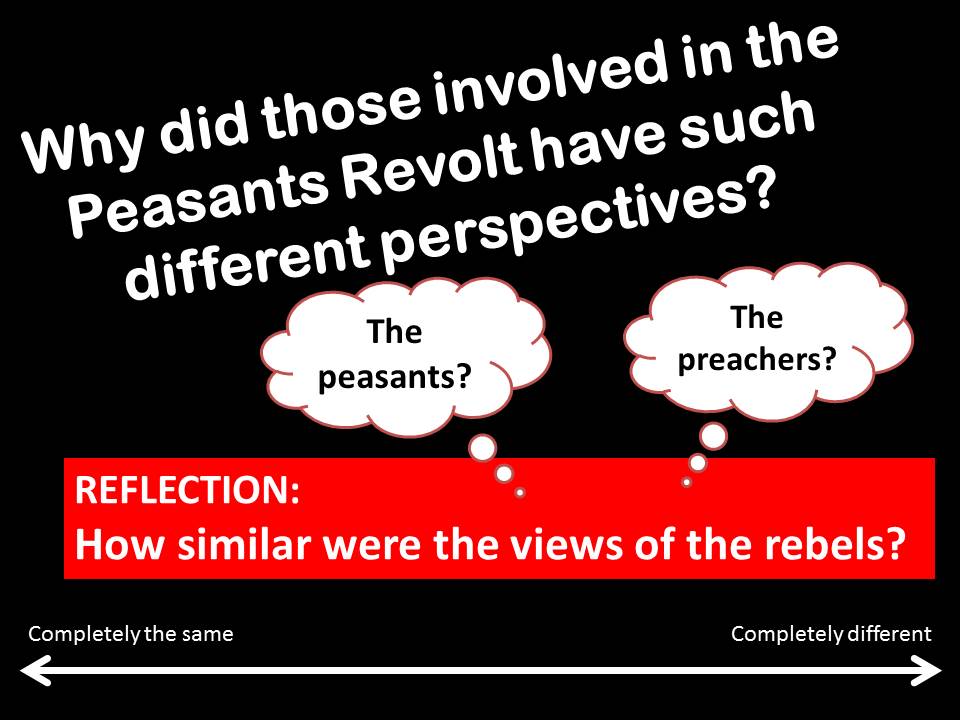

Understanding how language can improve their historical writing is really important for students if they are going to progress. Using continuums to ‘fine tune’ the accuracy of their claims has been crucial in getting stdents to create higher level responses. Take the following example:

Students were now able to explore the extent of the similarity or difference and not just that it existed. Students were able to move beyond sentences like, ‘The rebels were similar,’ and create ones like, ‘The peasants and John Ball were fairly similar in their views about freedom, because they both strongly believed in peasants having more rights.’ Linking language to the development of subject writing and explicitly showing students ‘how’ it all works, means we can move away from surface understanding and embed the principles. The impact is then long lasting and allows students to reapply their learning in future situations.

The last level in my Differentiation quest involves deconstructing historical skills and writing still further so that students can begin to understand what it really involves and how they can make it fit together.

That will be the subject of the third and final post…