‘Critique in most classroom settings has a singular audience and a limited impact: whether from a teacher or peer, it is for the edification of the author; the goal is to improve that particular piece. The formal critique in my classroom has a broader goal. I use whole-class critique sessions as a primary context for sharing knowledge and skills with the group’ (Ron Berger, An Ethic of Excellence)

When I first read Ron Berger’s work on critique I was blown away: he was able to get students giving detailed and almost professional feedback to others so that work was substantially improved as a result. To me, this seemed like an ideal that was practically out of reach. Like the vast majority of teachers I have used AfL strategies that ask students to comment on the effectiveness of work and, I suspect, for most of us the results were disappointing. Comments were too general and therefore difficult to act upon. Even with modelling and practice, the quality was still a way off where I wanted it to be. Take a look at these videos by the man himself explaining its purpose and power:

Critiquing has changed my attitudes and transformed the quality of work in my classroom. Of course, there are other factors that have helped with this (for example, project based learning, SOLO taxonomy and Big Questions), but critiquing deserves the spotlight as a strategy that can have a profound impact on learning. It is high risk and takes time to master, but I have been so impressed with the results. Asking students to put their work up for public scrutiny is a bold move, asking them to listen patiently as others coolly dissect their work is difficult for some. It is difficult for teachers too, relying on a whole class to come to with quality comments with just a few prompts from you. However, it does work if approached in the right manner.

So, here are my ‘Top Five Tips’ for successful critiquing:

1. Establish the right culture

You need to get across the message early on that a piece of work is not an end in itself, but a stage in a longer process. Quality takes time and students need to get away from a checklist driven mentality and move to one of continual improvement. This will probably be a struggle at first, as students used to the former. Also, you have to ween them off their grade/level dependency (it only makes their checklist addiction stronger). I agree with Berger when he tells students there are only two grades in his class: ‘A’ and not done.

I have launched this concept in two ways. Firstly, I have quotes on my windows that read:

“What could you possibly achieve of quality in a single draft?”

“Would you ever put on a play without rehearsals?”

“Would you ever play a gig without practicing first?”

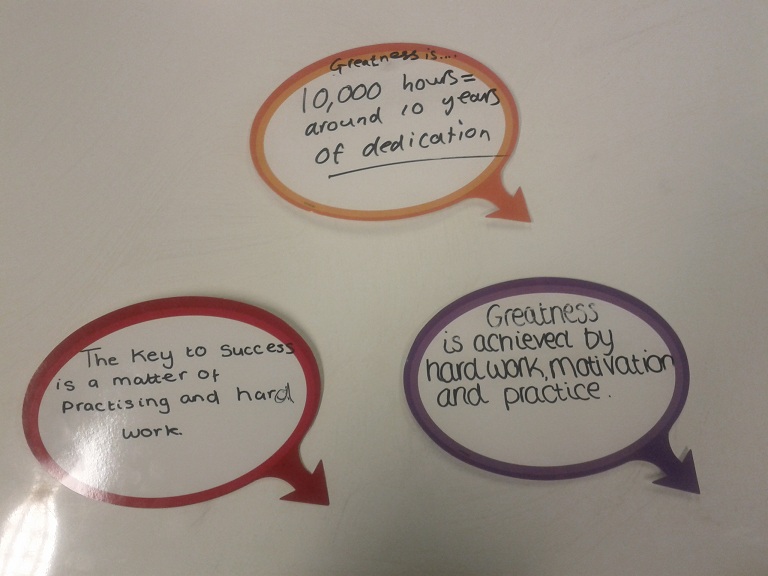

The purpose of these quotes (straight from Berger) was to establish, in terms relevant to them, why drafting is needed. I then moved into the more abstract and asked students to consider an article from the Big Issue about what made Usain Bolt great (Issue #966). From this they pulled out their favourite quotes (see image above) and we made a display. I did this same activity with all groups from Year 7 to Year 13 so that the message was absolutely clear.

2. Go Over the Rules… Every Single Time

From the Work at High Tech High, via Darren Mead, I got the following rules:

– Hard on content, soft on people

– Step up, step back

– Be kind, helpful and specific

(Click on the rules for Darren Mead’s excellent dissection of how they work).

These have been crucial in making critique work. By making the whole AfL experience public, it is easier to spot weaker comments and ask students to clarify or provide specific examples. Also, the idea that everyone should be involved has been crucial. In most instances, the process has been contagious and students have responded well. The last rule sums up everything else and gets to the heart of why the process is so powerful. Practice has shown me though that rules need to be established before every critique. Year 9 will soon be doing their fourth of the year and I will go over the rules carefully; it reinforces the expectations and shows them that it is a serious business.

3. Aim for perfection and insist on quality

The first few times that I used critique I treated it too lightly. I wanted to establish the concept of it with students and so allowed them to get away with comments that were not that in depth. This was completely wrong. Critique works best when it works towards quality. It has to be the goal of every session, even if it seems hard or harsh. You might need several sessions of critique to get the desired product, but it should always be there as your aim. This is why I gave Year 13 an article aimed at Cambridge students, written by a leading academic, as an example of what I was looking for. That is the level I want them to reach and their critique of each others work was centred around making this a reality.

4. Critique a Variety of Media

With some groups I made the mistake of critiquing two pieces of written work with them early on. In their minds the process became synonymous with that media, rather than as Berger says ‘a habit that suffuses the classroom.’ Therefore, I have tried to ensure that we look at least two different media early on so that they understand that the process of critique is about attitude and not just about writing. Below are the first two drafts of an Audioboo completed by a mixed ability Year 9 group in order to answer to the question ‘Why did Wilf go to war?’:

After the first recording we critiqued the work and the students talked about the need to offer specific information to back up points and they also wanted to have better explanations. There was a lot of discussion about what specific information was relevant. The second draft is below:

There are two obvious differences between the two drafts. The first is length; the second attempt is almost two minutes longer and therefore includes much more detail. However, the most impressive thing is the amount of students who joined in the second time around. Many more wanted to add some details or an explanation and it became (almost) a whole class piece. Next lesson we will go back to this and critique again to make further improvements.

Audioboo and critique of exhibition pieces have stopped critique from becoming stale and allowed my groups to grasp its true purpose: helping them to achieve quality.

5. Only critique work when it is ready

At first, I tried to critique a whole class at the same time. It was hard to keep the pace going and also it was too long. This approach worked fine for sixth form where numbers were smaller and patience longer; in fact, when Year 13 critiqued their opening paragraph to an essay it was incredibly beneficial as we could identify several key features of a good answer and share excellent examples of knowledge to back up points. Looking back though, the reason it was so successful is that everyone had a paragraph that they were ready to share. Critiques where lots of students need to share work often fail because of variation in the amount of work they have achieved. Therefore, I have been working hard to find ways to minimise this.

Lower down the school I have tried several things to ensure that critiquing is more fluid and focused. With Year 9 I trialled critiquing someone’s work at the end of each lesson. This has created a really healthy attitude among the group, although we quickly extended it to cover two people (less scary and more opportunity to develop key principles of what we are studying). With Year 8 I have critiqued segments of a whole: We ask different people to present one part of the work and then stitch the bits together to make a whole. Then, we can critique the whole product. This gives us a range of opinions and answers, but also allows us to focus on the principles of an effective piece (the Audioboo recordings above are a good example of this).

Sometimes you need to see all the work. Post-its are great for allowing everyone to contribute, but it still needs for you to bring back the discussion to a central place and establish the key features. After a Post-it activity, questions like ‘What features did you see a lot?’ and ‘What advice were you writing often?’ are good to get the discussion going.

To recap, if you want a whole class to successfully critique the work of other students it is a good idea to…

1. Establish the right culture

2. Go over the rules… every single time

3. Aim for perfection and insist on quality

4. Critique a variety of media

5. Only critique work when it is ready

If you need further proof, I used critique in a lesson observed by an HMI. I said six words in the 30 minutes they were there: “Get yourself ready for a gallery critique.” They were very impressed.